Tags

Aponte Literary, Books, Charles Kiernan, Folklore, Grimms Fairy Tales, LehighValley Storytelling Guild, National Storytelling Network, National Youth Storytelling Showcase, Storytelling, The Goose Girl

When was the last time you read, or heard someone read, a real fairy tale? Did you know the Brothers Grimm printed over 200 stories, but most of us are aware of only a handful? Centuries ago, fables were told by word of mouth, perpetuated by folks who couldn’t read, or couldn’t afford a printed version. When the Brothers Grimm collected and published popular folklore in the nineteenth-century, it opened a completely new door to literary romanticism in Europe.

Fellow Aponte Literary author, Charles Kiernan, is one of those rare talents that can hold an audience captivated with his storytelling, no matter how many times you’ve heard the tale. It isn’t just the words, it’s how it’s told. I had the privilege last month of listening to Charles dissect the elements of a traditional fairy tale. He was kind enough to share this knowledge on Searching for Light in the Darkness.

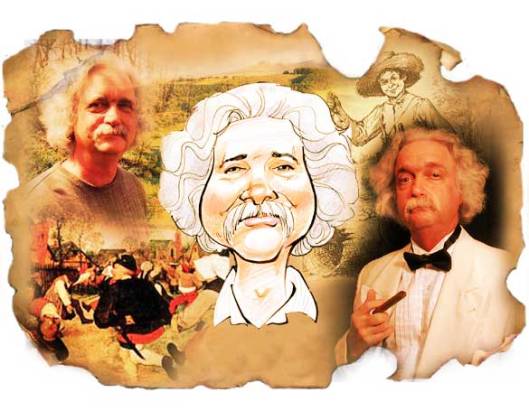

And yes, his resemblance to Mark Twain is uncannily accurate.

*****

I am going to take apart a fairy tale (I don’t think any harm will come to it from my doing so) to see what makes it tick. Below is a piece from the Brothers Grimm’s – The Goose Girl.

She [the queen] likewise assigned to her [her daughter] a chambermaid, who was to ride with her, and deliver her into the hands of the bridegroom. Each received a horse for the journey. The princess’s horse was called Falada, and could speak. When the hour of departure had come, the old mother went into her bedroom, took a small knife and cut her fingers with it until they bled. Then she held out a small white cloth and let three drops of blood fall into it. She gave them to her daughter, saying, “Take good care of these. They will be of service to you on your way.”

The characteristics listed below are reflected in the paragraph above and shared by all traditional fairy tales:

- Few characters have names. Typically, they are identified by their position—king, queen, youngest son, old soldier. In my example, only the horse has a name, not the people.

- Descriptions are sparse. We are told little of how things look.

- Tales are in the third-person objective. We never get inside the characters’ heads.

- Tales are not dialog driven. Dialog is used to highlight parts of the story.

- There is more telling than showing. Showing is a wordier process than telling. Telling is succinct, as are the tales.

Moving beyond basic style to content and motifs:

- There is a propensity for the number three. In The Goose Girl we see three drops of blood. Later on in the story there are three streams to cross, and three passages through a dark gateway.

- Royalty have magical powers. This is always assumed, perhaps a reflection of the times.

- Animals can talk, and not simply animals talking amongst themselves, but also animals talking to humans.

- Evil must be punished and good rewarded. Typically, evil is destroyed in rather graphic terms.

- The story ends happily. You can have a fairy tale without fairies, but not without a happy ending.

When we step back, a tale like The Goose Girl is full of nonsense and improbabilities.

Two women, one a princess, carrying a valuable dowry, travel without a bodyguard. At the banquet, the false maid, the story’s antagonist, fails to recognize the princess, whom she knows well. The maid is improbably dense and does not see the fatal set-up coming. My critique group would eviscerate me for such clumsiness if I had written this tale.

Do fairy tales get away with these odd forms because the stories are serving psychological underpinnings?

For example, Bruno Bettelheim suggests in The Uses of Enchantment that the evil stepmother evokes a child’s conflicted feelings toward his or her real mother in a one-step-removed safe environment. A child can feel anger toward the evil stepmother that is not safe to feel otherwise.

That notion works if we look only at the Grimm brothers’ tales, as did Bettelheim. If we check the versions from which the Grimms adapted these tales, it is the mothers who try to kill their children; not nearly so safe.

There is a better explanation for the fairy tale’s form. The original, illiterate storytellers were not familiar with literary conventions. The story format they and their listeners knew was the structure of their dreams.

We, literate though we are, still recognize the surreal in these old stories, and we suspend logic. Fairy tales are the closest things we have to waking dreams.

*****

Storyteller Charles Kiernan performs at theatres, listening clubs, schools, libraries, and arts festivals. He is the recipient of the 2008 Individual Artist Award from the Bethlehem Fine Arts Commission, Pennsylvania State Representative for the National Youth Storytelling Showcase, Pennsylvania State Liaison for the National Storytelling Network, and Coordinator for the Lehigh Valley Storytelling Guild.

He loves to tell the Brothers Grimm and other fairy tales. But, be warned, he does tell them in their original spirit, under the belief that the “grimness” of Grimm serves a purpose, and should not be removed.

You can find him at:

Also, be sure to follow his blog:

Fairy Tale of the Month – Reflections and Delusions

Thanks Charles for watching over my site last week, and teaching us all how fairy tales of yesteryear were constructed.

The Goose Girl was one of the first fairytales that at once horrified and entranced me; the other being one of the 1001 Nights Tales (the one with the three dogs). Nowadays I rewrite fairytales, which pleases me immensely 😀

Yes, Goose Girl is one of my favorites too. How can a talking horse’s head not pull you in.

This was fascinating–and I found the original Grimm tales, very “grim” indeed. And the happily ever after was sometimes strange. I like how you broke this apart. I must ask, what is your favorite Grimm tale?

My stock reply to the question of my favorite tale is: The one I am telling right now. The ones I find myself coming back to over and over are: Fisherman and his Wife, Juniper Tree (those two given to the Grimms by Philipp Otto Runge), Three Little Gnomes, Goose Girl, and The White Snake. But then I am leaving out Old Rink Rank, and…

Excellent! And very good point “The one I am telling right now.” I most certainly agree!